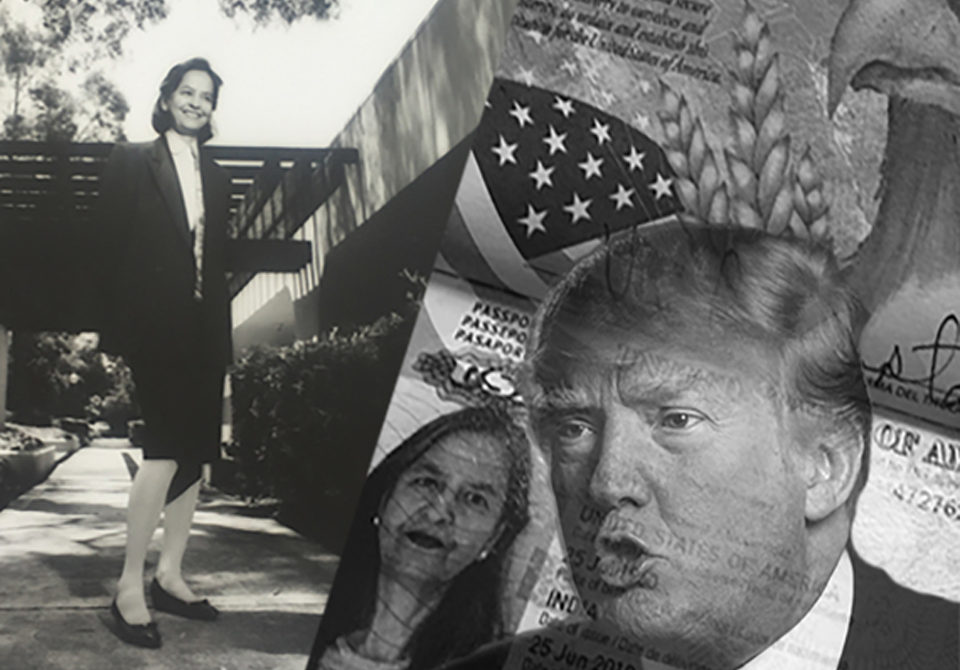

Silicon Valley is a place where boundaries of race, color, traditions, religions melt, and the multiplicity of cultures strengthens the fabric which has fueled America’s economic engine of innovation. It goes against the grain of Siliconiers, with the upcoming presidential primaries in California, when Donald Trump declares that he “will make America great by building walls, by keeping Muslims out and bringing jobs back to America through reduced work visas.” He is okay operating on the edge of legal boundaries, filing for bankruptcies numerous times without remorse, which we find not quite acceptable.

Here is a story, and it’s my story. I was raised in India, but I am essentially a product of Silicon Valley. I arrived here for higher education and then followed my dreams in the Valley, like many other immigrants-turned-entrepreneurs. The acceptance, the inclusiveness, the opportunity, and the integrity of the Valley is magnetic and has upheld my idealism and has molded my thinking. When I graduated from UCLA with a master’s in electrical engineering, I was the only woman in my class.

“When I graduated from UCLA with a master’s in electrical engineering, I was the only woman in my class.”

It was not easy for me to assimilate and integrate in America for almost 10 years, both culturally and because I remained one of few women amongst my colleagues for almost a decade. Nine months after my arrival in the US, I completed my master’s degree with a 4.0 GPA. Yet it was not easy to find a job, because I did not have a work visa and needed an employer’s sponsorship. I went for my job interviews in a sari because that was the most formal article of clothing that I owned. My attire, Indian accent, and lack of work visa were definite impediments, but did not stop me from landing a job at GTE Lenkurt in San Carlos, at the boundary of the then Silicon Valley just two towns north of Palo Alto.

“My attire, Indian accent, and lack of work visa were definite impediments, but did not stop me from landing a job…”

The Valley’s culture imbues authenticity which immigrants and locals equally embrace. At GTE, I was told that I was the highest-paid of the 13 new graduates hired that year. GTE did not low-ball my offer even though I could have been had for much less. Later I worked for another company for eight more years but left when I was passed over for promotion which I felt I deserved. In my exit interview, the representative of the personnel department asked me if I thought that I had been denied the promotion because of my gender. I replied, “No, the other guy politically outsmarted me but I was the more capable candidate.” They did not hedge or beat around the bush nor did I take advantage of them.

After this disappointment, I started my own technology company, Digital Link, with a coworker. I would become the first Indian woman to take a company public. When I started the company, people came out of the woodwork, people without whose help we would not have succeeded. A product manager at Northern Telecom, took special interest in getting our product approved. Selling the product to Northern Telecom and its customers, alleviated the pressure to raise immediate capital. He is still a great friend, after more than 30 years.

I hired Digital Link’s first manufacturing manager with a small advertisement in a local newspaper. He took over the building keys, the day he walked in. Our first accounting manager, a 27 year old white American took over the checkbook. Our first VP of R&D, another young American became my confidant and business partner. Summit Partners, a VC firm, funded the company knowing I was pregnant with my first child. They had the kind of integrity that I did not know existed. Their morality and support along with market opportunity helped propel my company to IPO. As an immigrant, I combined my nimble disposition and my hunger for recognition with American ethics to design innovative products and services.

Silicon Valley is also a hot spot of reengineering an enterprise as technology develops and becomes obsolete just in the span of a few years. Entrepreneurs are die-hard people who refuse to give up. My company suffered a major set back when WorldCom, our largest customer filed for bankruptcy. They cancelled the orders on the books, and no more future orders were expected and we had to eat up their inventory at hand. We never recovered. Yet we struggled for over five years, and when we finally decided to close the doors, we refused to file for bankruptcy. We felt moral obligation to pay our employees, the banks, and the vendors, with some money coming from our own pockets. This is what entrepreneurs in the Valley do.

Donald Trump’s thinking does not jive with this framework. We need to decide how to keep American dream alive, like in Silicon Valley, and to define what makes America great.